Dodge at Somerset House

Somerset House in London is set to launch an interactive artwork involving dodgems. (January 2021, covid permitting).

In Somerset House’s own words “Taking centre stage in the courtyard is a new interactive artwork from Anna Meredith, a Somerset House Studios resident and Mercury Award-nominated composer and musician. Bumps Per Minute sees the traditional fairground dodgems ride reinvented into a high-octane interactive sensory experience.”

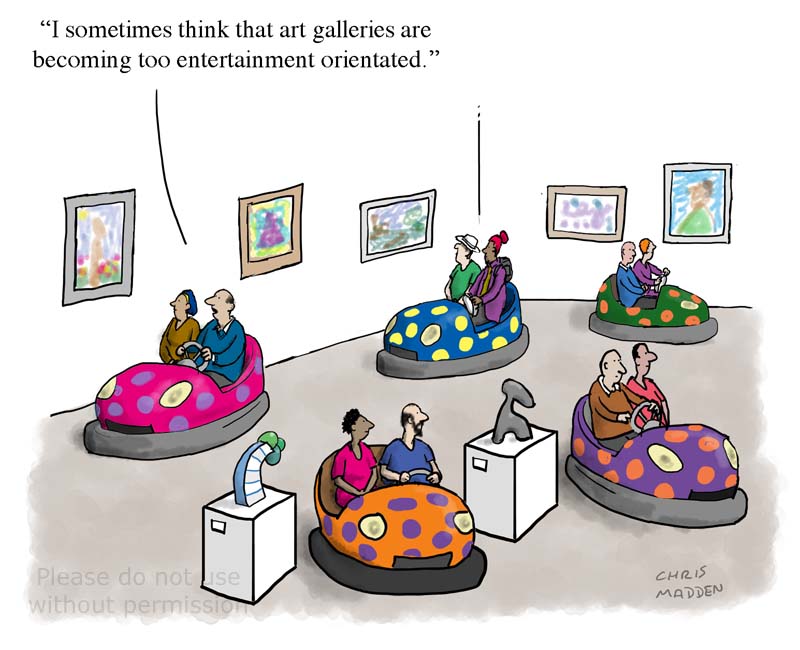

Below is a cartoon of mine from 2019, making an observation of the way that contemporary art is becoming more and more entertainment led. (Take for example the helter skelter slides by Carsten Höller that were installed in Tate Modern, and the children’s swings by Superflex that were also installed in Tate Modern a few years later).

See Dodge at Somerset House here.

Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens

A photo of a buzzard launching itself into the air from one of the sculptures in Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens, near Penzance, Cornwall.

The sculpture is Restless Temple by Penny Saunders (It sways disconcertingly in the wind).

The evolution of butterfly eyespots

Here’s an interesting observation I made a few years ago that I think makes a good illustration concerning the evolution of eyespots on butterfly wings.

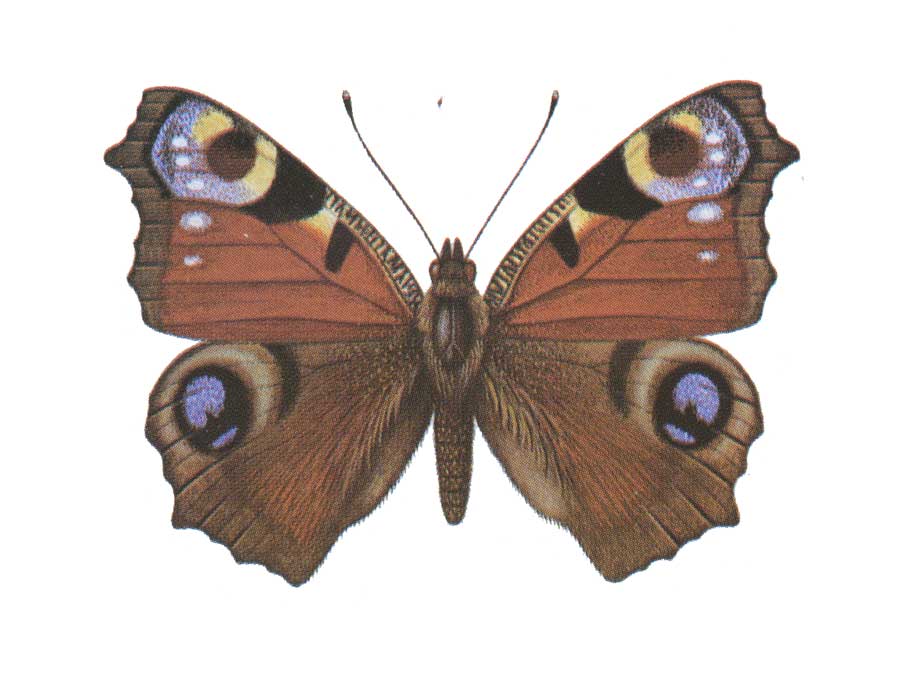

Below is an image of a peacock butterfly, with its very obvious eyespots.

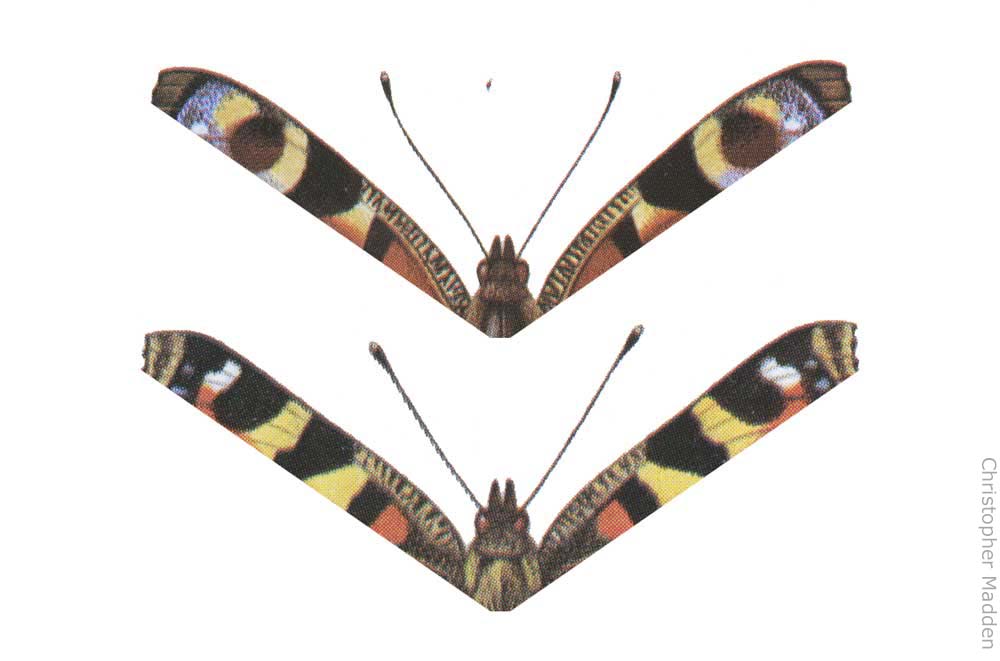

Next, here’s an image of the top edge of the peacock’s upper wings, with beneath it an image of the top edge of another butterfly’s wings that look extremely similar. You can make out the same type of eyespot pattern on both sets of wings.

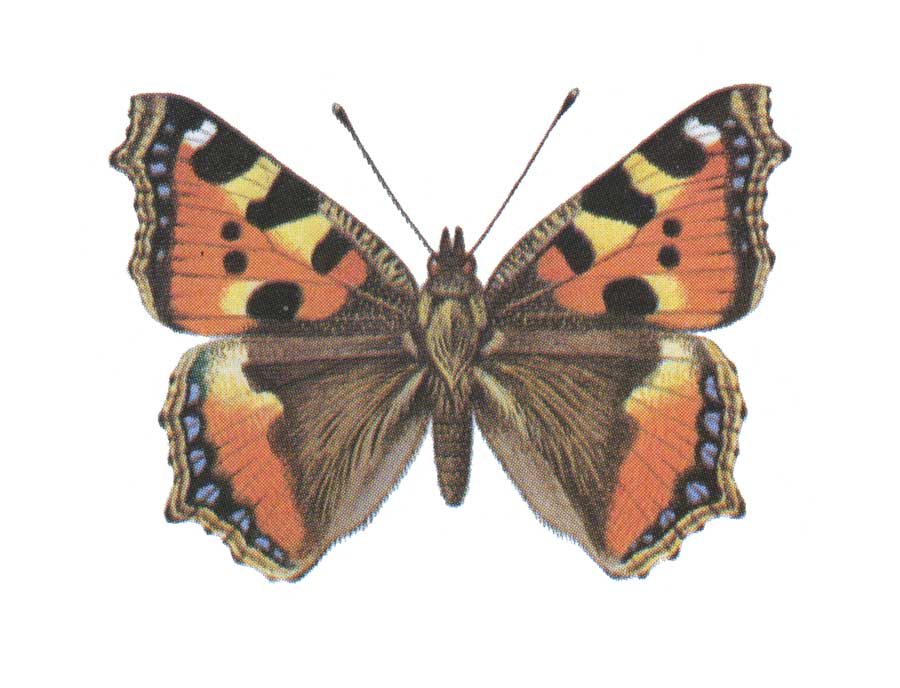

The second butterfly in the image above isn’t a peacock however, as you can see from the image of the whole butterfly below. It’s a small tortoiseshell, and it doesn’t have eyespots, just irregular stripes.

Assuming that the two species evolved from a common ancestor, how is it that the butterflies might have evolved in such a way that their wing patterns (at least along the top edge) are so similar yet so different?

Here’s a theory.

The common ancestor of the tortoiseshell and the peacock probably started without eyespots – with wings that were perhaps quite similar in patterning to the present day tortoiseshell’s (at least in the region of the wings that we’re dealing with). Small variations to the colouring of the patterning on the wings of some of the butterflies then turned the irregular stripes at the top of the wings into something that could be vaguely interpreted as eye shapes. These eye shapes turned out to be very useful for the survival of the butterflies that possessed them, because of their affect on predators (possibly by scaring them or by diverting them in some way), and thus the eyespot pattern was passed on through the generations, with the butterflies with the most eye-like eyespot patterns surviving best and thus passing on their enhanced eyespots. Thus the evolutionary line that developed into the peacock diverged from the line that evolved into the tortoiseshell.

This explanation for the evolution of the eyespot echoes very nicely the theory of the evolution of the eye itself, in which random variations in a species’ makeup eventually lead to the evolution of what otherwise seems to be a near miraculous organ, the eye (See The evolution of the eye ).

It’s just about possible that evolution took a different route, and that the common ancestor of the tortoiseshell and the peacock actually possessed eyespots, and that through evolution the tortoiseshell gradually lost its spots for some reason. This however doesn’t explain how the common ancestor acquired its eyespots in the first place. I expect that it would have been through a process very similar to the one that I’ve just described.

The small tortoiseshell is a very common butterfly in my part of the world (the UK), right up there with the peacock, so the lack of eyespots on the small tortoiseshell doesn’t seem to put the butterfly at a disadvantage compared to its eyespotted cousin. So, there must be something about the tortoiseshell that ensures its success without the use of eyespots. What it is I’m not sure.

One last thing.

A while ago I was watching a peacock butterfly sunning itself on the ground. I was watching it through a pair of close-focus binoculars, so that I has a very close-up view of the insect. It was vibrating its wings, which insects often do when they need to warm up their flying muscles. Through my binoculars the extremely close-up view of the rapidly vibrating eyespots on the wings looked truly sinister and scary. If I’d been a predator (which by definition would mean that I’d be very close to the butterfly and would be very much aware of the vibrating of the eyespots) I’d have fled. So vibrating wings may not only be good for warming up wing muscles, but also for warding off predators (which would be particularly useful when the butterfly hadn’t warmed its wing muscles up enough to be able to fly away).

Below is another graphic showing the comparison between the eyespots on the peacock butterfly and the same region on the wing of the small tortoiseshell butterfly.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude cartoon

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: The Mastaba

The Mastaba by Christo and Jeanne-Claude on the Serpentine in Hyde Park, London, July 2018.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude are most well-known for wrapping things up, however they’ve also had a thing about oil barrels for quite a long time.

Below is one of their more modest barrel-based works, exhibited in the Serpentine Gallery until 9th September 2018.

Here’s a cartoon about Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain at Tate Modern – how to display a revered object

The current exhibition of work by Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dali in the Royal Academy features Duchamp’s most famous work, Fountain, displayed in an arrangement in which it rests on a large table-like display stand on which in jostles with many other pieces of three dimensional art by the two artists (including Dali’s lobster telephone and Duchamp’s bicycle wheel).

This is in huge contrast to the way in which the work is normally displayed in Tate Modern, where it has stands in glorious isolation like a revered religious relic. The photo below of the Tate Modern display hopefully gives some impression of the reverence that the work inspires.

Olafur Eliasson at the Frieze Art Fair, London.

I’ve been a regular visitor to the Frieze Art Fair in London’s Regents Park for many years now.

In some years one particular work of art will stand out as my favourite.

This year it was a work by Olafur Eliasson.

Last year it was a work by Olafur Eliasson, and the year before that it was a work by Olafur Eliasson too.

In none of those years did I know that the work that I was admiring was by him when I first saw it – it was only when I looked at the labels afterwards that I realised that they were all by the same person.

Here’s this years example, titled The hinged view, exhibited by the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

Oxo Cube – an infinity mirrors artwork

This is a piece of contemporary art that I’m working on composed of a cube in which the vertical sides are all mirrors with their reflective surfaces facing inwards.

The multiple reflections that are created by the mirrors make the patterns on the floor of the cube seem to form the word ‘OXO’ in each corner of the cube, with the word itself then multiplied many times by the process of infinite reflection that is set up when mirrors are facing each other and are parallel.

The design on the base of the cube is shown below. The word ‘OXO’ doesn’t occur at all. It is the fact that the word OXO is symmetrical about both its horizontal and vertical centre-lines that allows the shapes in the cube’s base to be reflected and then reflected again to generate the word.

The ‘infinity mirrors’ nature of the work, with its infinite reflections within the cube can be seen in the image below.

The Path by Michael Puett, and the fallacy of the True Self

Harvard professor Michael Puett, who runs a course in classical Chinese philosophy, has recently co-authored a best-selling book, The Path, along with author and journalist Christine Gross-Loh

The Path presents ancient Chinese philosophy as a guide (or path) to how to lead a fulfilling life in the modern world,

It sounds like a standard pseudo-spiritual self-help book, but Puett insists that if anything it’s the opposite: it’s an anti-self-help book (although its very title, The Path, and its subtitle, What Chinese Philosophers Can Teach Us About the Good Life, makes me have my doubts). It does however stand against the current self-help trends for promoting atomised individuality and self-centred solipsism. The book is also critical of navel-gazing ‘mindfulness’, the authors pointing out that in Buddhism, mindfulness was originally intended to break down the self, but that in the western version of Buddhism it’s often been distorted as a way of looking inwards and embracing the self.

One of the concepts that is pursued in the book is the fallacy of the authentic self. I’m a big fan of this concept (the belief that the authentic self is a fallacy, that is – not the concept that there is such a thing as the authentic self), so here are a few of my thoughts on it.

The concept of the authentic self postulates that everyone has a core being or self that is somehow their true self – a self that is invariably superior to the version of themselves that functions in the everyday world (The everyday functional self is, after all, inevitably corrupted by the messiness of the real world, while the true self is in a state of pristine and pure isolation).

This is a nice conceit, with its attractive inference that everyone is at heart nicer than they seem. However, the very fact that this concept implies that we’re all quite pleasant people underneath should ring a few alarm bells in the self-delusion department.

The truth is, I think, that people are the sum of their interactions with the world: without the world we are nothing but a mass of cells and bio-electrical circuitry. Our ‘selves’ are an accretion of reactions to phenomena outside ourselves, such as our environments and our relationships with other people. It’s true that our reactions to these phenomena are laid down onto individual brains that are all structured differently to each other due to genetic variation, meaning that each individual will have a propensity to react differently to the world and to the experiences that it throws at them. I like to think of this genetically determined structure within the brain as a sort of ‘mind skeleton’ that is used to support the mind or self as it is constructed over the years as the result of experience, in a similar way to how the physical ‘body skeleton’ supports the body as it develops over the years (for better of worse). So I’m afraid that underneath the functioning self with which we interact with the world we don’t have a core ‘true self’ at all, just a rather fancy arrangement of scaffolding.

.

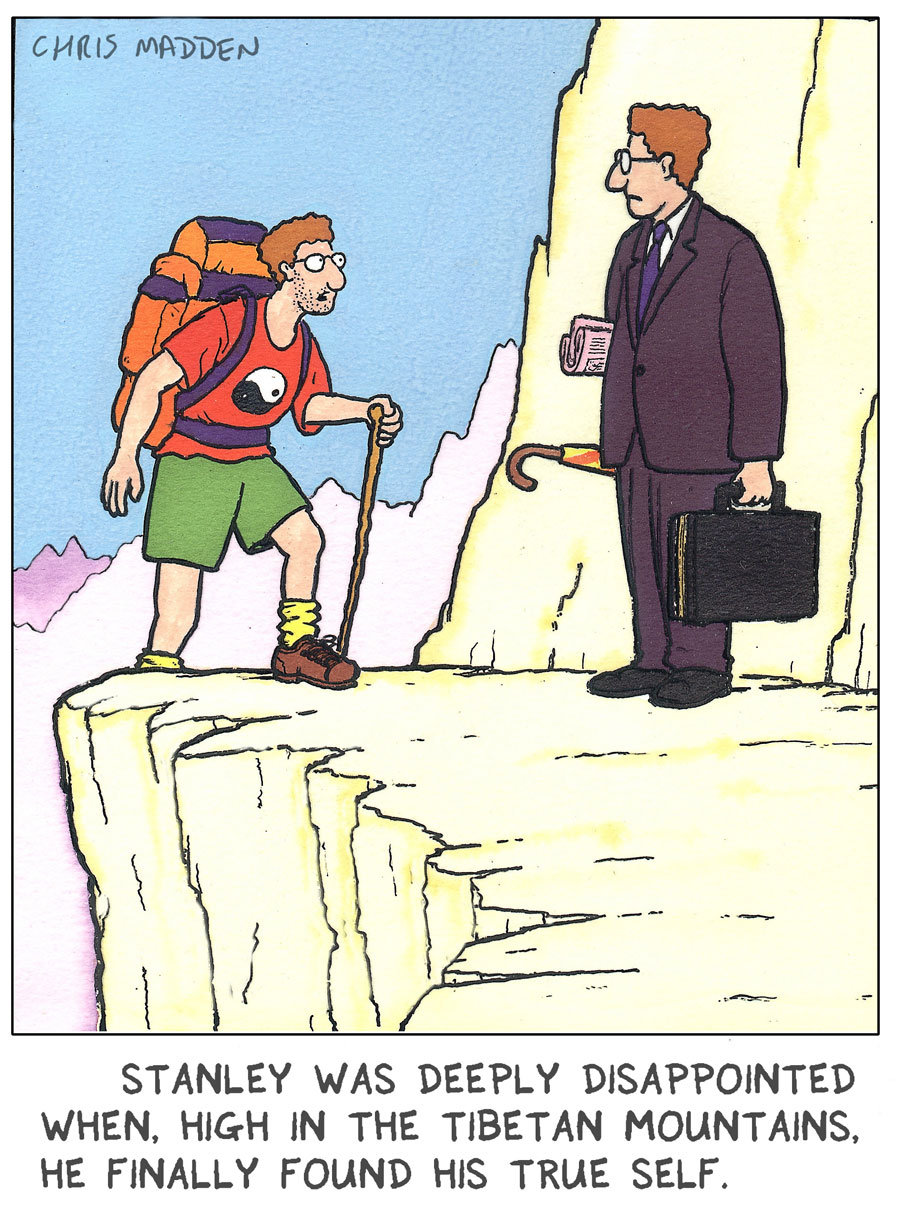

Here’s a cartoon that I drew in 1994 on the subject of finding your ‘True Self’ (I’ve held opinions on this topic for quite a few years). It was published as a greetings card by Paperlink.

Here’s another cartoon on the subject:

There’s a bit more on this subject in my book, Where Are We, Why Are We, What Are We? (And Why do we Want to Know?) , as detailed here.

.

What are the odds that you exist? The fallacy of your specialness.

What are the chances that you exist? That is, you personally.

I’ve heard this question posited many times.

I think Richard Dawkins mentioned it in one of his books, or maybe in an interview, and I’ve recently seen it on the back cover of the new book by Dr Alice Roberts titled “The Incredible Unlikeliness of Being“, (the book that gets my prize for the wittiest book title of the year, being based, in case you don’t know, on the book title “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” by Milan Kundera).

The question is usually asked in something along the lines of: what are the chances that your mother and father would meet? Maybe your mother turned left instead of right at a street corner and bumped into the man who was later to become your father. What are the chances of that?

And what are the chances that your grandparents met, and that their parents met, and that their parents met before them?

The chances are surely vanishingly minute.

Yes they are.

Your existence is statistically almost infinitely unlikely.

(Hence the title of Alice Robert’s book, The Incredible Unlikeliness of Being.)

However, as incredibly unlikely statistically your own personal existence is, it isn’t actually incredible in the sense of being beyond credibility.

As far as I can work out, the statistic concerning the likelihood of one’s own existence is a trivial or mundane statistic – in that it may be true but it has little significance.

Here’s an analogy to show what I mean.

I’m going to type a list of thirty random numbers.

386720635284219760463584372974

There it is.

Now, what are the chances of that row of numbers being those particular digits in that particular order?

The chances are one in 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

(A simpler example of the same principal is that the chances of writing any specific list of digits that’s only two digits long is one in a hundred – the combinations being from 00 to 99, or in other words a hundred possible combinations.)

You probably don’t think that it’s incredible that I’ve just written down a list of numbers that has only a one in a million million million (etc) chance of existing. I had to write down a list of thirty digits after all, and every list of thirty digits has the same incredibly low chance of being written. But one of them is inevitably going to be written.

It’s the same with people.

The chances of you existing may be almost vanishingly unlikely, but if it wasn’t you who existed it’d be someone else, in the same way that if it wasn’t that list of thirty digits it’d be a different one. (Your mother may have turned right at the street corner instead of left and bumped into a different man who would father a child who wasn’t you, while your father (who now wasn’t bumped into) continued on his journey to a work appointment at which he would meet his future wife).

We’ve got to end up with someone rather than no-one. It just doesn’t have to be you.

Or if it doesn’t have to be someone it has to be something. Maybe a descendant of the dinosaurs (because the asteroid missed), or more likely something that we can’t even envisage because there are just so many possibilities – just as there are so many possibilities when it comes to writing random thirty digit lists of numbers.

We haven’t even considered random million digit lists of numbers yet. Let’s not bother – just because something’s vanishingly unlikely doesn’t make it special.

Yayoi Kusama: The Passing Winter at Tate Modern

One of my favourite pieces of work in the new Switch House extension to Tate Modern is The Passing Winter by Yayoi Kusama.

This had a lot to do with my fascination with art that is based on mirrors.

The work is a hollow cube about a metre square, with the walls being composed of mirrors both inside and out. The mirrors are pierced with circular holes that allow the observer to peer into the cube and to see the internal mirrors. The internal mirrors reflect each other, and thus each reflection in each mirror reflects the reflection in the mirror, which is reflecting the reflection and so on, creating a sequence of reflections that would continue infinitely were it not for the physical constraints on the mirrors (such as the fact that with each reflection a small amount of brightness is lost, making each reflection slightly dimmer than the previous one).

A recent visit to the gallery confirmed that it’s not just me who’s fascinated by mirrors.

The room that houses The Passing Winter contains a fair few other worthy pieces of contemporary art, but none of them drew the gallery-goers’ attention in quite the way that Yayoi Kusama’s work did. It was the one piece of art around which people hovered in small animated crowds. People studied the other art in the room in quiet contemplation, but when the same people approached the The Passing Winter their moods changed to ones of outward engagement. And out came the cameras.

One of the lures of The Passing Winter is obviously that the spectator is reflected in the artwork, thus effectively becoming part of the artwork itself. Everyone’s interested in themselves, so everyone’s interested in this artwork. Especially when they themselves are part of it.

I’m sure that some critics may dismiss the work because of its crowd pleasing tendencies – accusing it of being dangerously close to a fairground attraction, with its appeal being partly to the audience’s baser narcissistic tendencies – a criticism that’s sometimes levelled at Anish Kapoor’s distorting mirror pieces.

But then quite a lot of art panders to the narcissistic tendencies of its audience, if only to massage their feelings of self worth, so I don’t see that as a problem.

The photo of The Passing Winter on Tate Modern’s own web site shows the work in isolation, with no one looking at it. This makes the piece look a bit inert and doesn’t convey anything of the dialogue between the work and the audience. I hope that my photos show the enlivening effect of the work.

When I first encountered this work I wasn’t aware of who the artist was, so I was pleased when I discovered that it was Yayoi Kusama, an artist whom I already greatly admired. She’s probably best known for her ‘polka dot’ artworks – her obsessive application of coloured dots to everything that she encounters (In 2012 Tate Modern staged an excellent exhibition of Kusama’s work, their only mistake being to stage it at the same time as an exhibition of Damien Hirst, forcing an inevitable comparison between Hirst’s dot paintings and Kusama’s polka dots. Rightly or wrongly, Kusama’s obsessive polka dots made Hirst’s ranks of uniform dots look rather lazy).

It was probably at that exhibition that I first came across Kusama’s mirror rooms which, as with The Passing Winter, used the device of parallel facing mirrors to create the effect of infinite regression. It’s a common enough phenomenon (you can see it in mirror lined department store lifts any day of the week), which I remember being fascinated in during by student days many years ago, however Kusama was the first person whose work I’ve seen who’s been able to harness the effect at the level of the sublime.

I suspectt that it’s because of her mirror based artworks that I’ve embarked on my own explorations of the genre, complete with infinite regression, as you can see here – mirror based art.

Contemporary art: mirror based art

This is an example of my own art. To see more please go here.

A study of mirrors and reflections using everyday objects, in this case screws from a hardware shop, to create interesting formations.

The screws are arranged in a quarter circle in the right angle between two mirrors to form a dynamic circular configuration.

Screws lend themselves to this study partly because of their physical qualities – being large at one end and tapering away at the other, with their interesting screw thread along their lengths – and partly because of their intended purpose, which is to hold things firmly in place (which is the exact opposite of the dynamism that they hopefully exhibit in this work.

Contemporary art: mirrors, reflections, illusions.

This is one of my artworks. To see more please go to my contemporary art site.

One of my contemporary art projects exploring mirrors, reflections and illusions. This experiment incorporates a piece of brightly coloured nylon cord that is reflected several times to give the impression of a closed complete circle.

This work is composed of three mirrors facing inwards creating a triangular box. The box is placed over a length of brightly coloured nylon cord. The cord is placed more or less randomly except for the part that lies inside the triangular box which is reflected on the box’s sides to give the illusion of forming a circle. The second photo shows the piece from a different angle to give an idea of the structure.

For more of my contemporary artworks click here: contemporary art

New BBC 3 logo criticised

The new logo for BBC 3 (shown below) has been criticised for supposedly not including the number 3.

Personally I like the logo.

To me the number 3 is clearly there in the form of the Roman III. The fact that the final digit is also an exclamation mark is a clever typographical trick, not a design blunder. It might have been a blunder a few decades ago, when the design would possibly have been interpreted as II!, but in these days of hybrid symbols I’m not so sure, especially when it’s viewed at the very small size that it’s designed to be viewed at (unlike here).

The three digits of the Roman III also echo the three squares of the BBC logo above, creating a nice unity.

The design contains something of the concept of modifying digits to convey a message within the digits themselves. In this case that BBC 3 is fun and youthful.

Another example of this style of typography is the logo for Channel 4 Plus One, the version of Channel 4 that is broadcast an hour after the original. Its logo, shown below, consists of a plus sign and the number one that can also be read as a subtle number 4.

.

.

Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall – and plant-based art installations

It’s interesting to see that the forthcoming installation in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall is a plant based work.

The installation, by Abraham Cruzillegas, titled Empty Lot, is composed of ranks of raised beds in which plants of various types are growing (At least I think that plants are growing in them – I saw the beds today and lots of them seemed to be noticeably devoid of life. However, the installation doesn’t officially open until next week, so there’s time yet).

I’ll say a bit more about Abraham Cruzillegas’s installation in a few weeks’ time, when it’s fully functioning.

The reason I’m mentioning it now, a little prematurely, is because the plant based nature of the installation reminds me of a Tate Turbine Hall installation that I devised myself, shown in the photos below. This installation has never actually existed in real life, being a figment of my imagination.

My installation concept is called Crocus Carpet and it consists (as you can hopefully see in the photo below), of the whole floor of the Tate Modern turbine hall being turfed over and planted with crocuses, with pleasant pathways meandering between the flowers.

Art is often concerned with questioning one’s perceptions, and that’s exactly what this work does. The sensation of strolling through what feels like an area of parkland that’s actually inside a huge cathedral-like industrial building is hopefully a little unsettling and disorientating.

.

However, Crocus Carpet doesn’t only make you question your perceptions solely by virtue of the fact that it’s an outdoor space that’s been transported indoors – it also does so because the crocuses aren’t what they seem. The following photo shows a small scale version of the same idea.

The crocuses are darts.

(This photo is of a real artwork of mine, created in 1995, in which inexpensive darts are positioned in a square of artificial turf with artificial flowers. The cheap and cheerful properties of the piece are part of its appeal.)

.

Here’s how the parts of the darts correspond to the different parts of a crocus.

.

Part of the appeal of Crocus Carpet is (hopefully) the way that it approaches concepts of reality, illusion, perception and deception – by utilising the dissonance arising from the similarity in appearance and the contrast in nature between soft, reassuring and comforting crocus flowers and hard, aggressive and potentially dangerous darts.

Here’s another version of the Crocus Carpet work, this time installed on the lawn outside Tate Britain. Again, this is a visualisation of the piece rather than being an actual artwork itself.

.

.

Finally, here’s another site specific version of the installation – this time installed in a (real) garden in Cornwall.

.

See more of my art on my site dedicated to my artwork.

.

.

The Rosetta comet probe – alternative designs for the Philae lander

The Philae lander has now left the Rosetta comet-chasing space probe and is heading for a rendezvous with the comet in six hours or so.

Watching television reports about how the probe is designed to land on the comet doesn’t exactly fill me with confidence. The three-legged design looks as though it wouldn’t take much to tip it over, and the surface of the comet certainly looks as though it’s littered with numerous trip hazards.

I can’t quite work out why the designers didn’t go for a more terrain-forgiving landing mechanism that had more latitude for error. Obviously there are issues of cost restraints and factors of technical feasibility that I know nothing about, but here are a few suggestions of my own.

Ideas that come to mind are such things as using a harpoon to anchor the craft to the comet before the craft actually touches down, then the craft could reel itself in no matter what the lie of the land. This method would obviously need the material of which the comet is composed to be harpoonable, which may be why the method was rejected. (The craft actually does have anchoring harpoons attached, but these are designed to be deployed after it’s landed, so they are more of a back-up system than a primary device).

Other landing systems that may have been appropriate could involve flexible or cushioning landing mechanisms such as inflated pillows (that deflate on impact), widely splayed, long, articulated legs (much more flexible and articulated than the rather rigid-looking ones that the spacecraft actually has) that buckle on impact to take on the topography of the landing site, or even the astronautical equivalent of long chains with grappling hooks that could fan out around the craft as it comes in to land to snag on any suitable features of the terrain.

In all of these designs the scientific instruments in the probe could be housed in a self-righting capsule to ensure optimum orientation after touchdown. The design of the probe that’s actually going to land in a few hours’ time doesn’t seem to have any system for realigning itself if it lands awkwardly.

Anyway, Philae is due to land soon, so I hope my misgivings prove to be unfounded. I’m sure the landing site that’s been chosen for the probe is the best possible site that’s available, so – fingers crossed!.

Why Women’s Menstrual Cycles are Linked to the Moon

Are women’s menstrual cycles affected by the moon?

A menstrual cycle does after all span the same amount of time as a lunar cycle. The word menstrual actually means monthly, and a month is based on a lunar cycle (so it should maybe be called a moonth).

Discussion about the subject often revolves around the fact that the moon creates the tides in the oceans, so logic suggests that it probably creates tides in people too, affecting their bodies in interesting ways – and affecting their brains too, such as turning some of them into ‘lunatics’ or ‘lunar-tics’ at the full moon.

This theory falls down due to the fact that the moon’s gravitational pull on objects on the earth is extremely small. It only affects the oceans to the extent that it does because there’s a lot of ocean to affect – so you notice the effect at the edge as the water goes up and down the beech. You don’t notice the tide in a puddle on the pavement after a shower of rain (and the puddle definitely doesn’t travel several metres as a single entity across the ground following the pull of the moon, covering the same distance as is covered by the tide on a beech). In fact the gravitational pull of a tree outside your house is much greater than the pull of the moon, so the pull of the moon is effectively swamped by everyday objects here on earth.

If the moon does have an influence on menstrual cycles I think that the reason is probably quite prosaic – it’s to do with the brightness of moonlight.

Why would the brightness of the moon affect menstrual cycles?

Because it affects what people in the days before the invention of artificial light could do at night.

The full moon lights up the night sky quite significantly (and conversely, the new moon results in ink black nights on which you can’t see your hand in front of your face). When there was a full moon people could move around at night; when there was no moon they couldn’t (or at least could only do so with much more difficulty). In our modern world we can easily forget this fact, but in the world before artificial light it had a huge impact on after-dark activity.

There are probably numerous scenarios that can by posited in which moonlight and the resulting nght-time activity of humans could play a part in influencing menstrual cycles – here’s one that I’ve devised (as I’m sure have others).

Primitive humans used to live in small family groups, often in competition over territory with neighbouring groups.

Within any particular group it would be common for males and females to mate. Unfortunately, because the member of the group were almost definitely related to each other one of the consequences of mating within the group would be in-breeding, with the resulting degeneration of the genetic stock. Ideally it’s best to mate with someone who isn’t a particularly close relative in order to ensure robustness in offspring due to genetic variation.

It would be preferable for a female in a group to mate with a male from a neighbouring group (even though the members of the two groups would probably all be related to each other to some degree, but not as closely as within each individual group). Unfortunately mating with a neighbour would probably be difficult due to the fact that the groups were in competition for land and resources to the extent that when the groups met the result would be conflict.

The only way in which a female from one group could mate with a male from a different group would be if they were to meet away from the gaze of other group members, and that would probably never happen while the members of the groups were wandering around during daylight hours when it was easy for them to keep an eye on each other.

Meetings between males and females from neighbouring groups were much more likely at night, when it was harder for group members to see what other group members were doing. Not only that, but meetings were much more likely on moonlit nights, when nocturnal activity was at its height.

As a result, females would be much more likely to bear offspring from members of neighbouring groups

following meetings on those moonlit nights.

How would this make women’s menstrual cycles synchronise with the phases of the moon?

In order for a liaison to bare offspring the female has to be fertile at the time of mating. As a liaison between a female and a male from different groups is more likely at the time of the full moon it follows that for such a liaison to bare offspring the female would have to be fertile at the time of the full moon.

The offspring of liaisons between members of neighbouring groups would, on average, tend to be more robust that the offspring of liaisons between members of the same group, and would thus be more likely to grow to adulthood and breed themselves. Thus the characteristics of females who are fertile at the time of the full moon would be more likely to survive into future generations – with one of these characteristics would be the tendency to be fertile at the time of the full moon.

Not only is it advantageous for a female to be fertile at the time of the full moon, it’s equally important for the female to not be fertile at other times of the lunar cycle, when she’s much more likely to mate with members of her own, related group. So, for instance, it would be a disadvantage to be fertile twice during the lunar cycle (especially as, for one of the fertile periods to coincide with the full moon the second fertile period would probably coincide with the new moon, when the sky is at its darkest and mating between members of the same group would be most likely).

I have to impress that I’m not suggesting that the appearance of the full moon in the sky would make the members of different groups actively go out and seek members of other groups to mate with (but equally I’m not saying that that wouldn’t be the case). All I’m saying is that the time of the full moon would be the time when members of different groups mated and thus had offspring who were more robust than the more inbred offspring of mating within the same group. The process involved is simply evolution at work. No special lunar powers are evoked or involved. It’s all to do with the slight advantages of genetic robustness brought about by the production of offspring from the larger gene pool that is available at the time of the full moon.

Are we alone in the galaxy? Brian Cox thinks so.

Is there anyone out there?

Are there other stars than the Sun in the galaxy that are orbited by planets that support intelligent life?

Brian Cox doesn’t think so.

In his BBC tv series on the human race’s place in the universe – Human Universe – he gives his reasons.

I’m not sure that I agree with him, but here’s his thinking.

In the 1940s Hungarian/American mathematician John von Neumann came up with the concept of self replicating machines (which he called universal constructors) – machines that could reproduce themselves. (Having just stated that von Neumann came up with the concept I’d like to qualify that statement with the observation that most concepts are thought up independently by several people, it’s just that only one of them usually gets the credit).

If such machines were to be launched into space they could land on asteroids, planets etc and mine the mineral resources there, using the minerals to construct replicants of themselves. By a process of asteroid/planet hopping they could thus multiply and spread out through the galaxy. It’s estimated that by such a process the whole galaxy could be colonised in ten million years.

If an intelligent alien race had at some point over ten million years ago (that is, for most of the history of the galaxy) decided to create such machines they’d have spread throughout the galaxy by now and we’d be able to see evidence of their existence.

But we can’t, so they didn’t.

This, according to Brian Cox, is the clincher when it comes to deciding whether advanced, space-going civilisations have existed before. He thinks that because the concept of self-replicating galaxy-colonising machines constructed by advanced alien civilisations is possible in principle we have to construct an argument for why we don’t see them – and he can’t think of any such argument.

He concludes that therefore it’s probable that there never have been advanced space-going civilisations in the galaxy up until now – until we came along.

Personally, I’m slightly uncomfortable with the reasoning here. The lack of evidence of self-replicating alien technology in our vicinity seems like a rather tenuous reason to dismiss the concept of intelligent alien life-forms.

In the tv programme Brian Cox stated that he couldn’t think of any reasons why where wouldn’t be evidence of alien self-replicating machinery, so I assume that he’s weighed up the arguments and has dismissed the ones that give reasons why advanced civilisation may exist and yet may not send out self-replicating machines. Unfortunately he didn’t give us any examples, which is a shame.

I can think of a few off the top of my head. They’re probably all flawed, but here are three of them.

Reason one: advanced alien intelligences have existed that are capable of making self-replicating galaxy-colonising machines, but they decided not to. They may have realised that a galaxy that was full of their machines, self-replicating endlessly – long after the civilisation itself had died out – was not a good idea. They’d probably have tried prototype self-replicating machines on their home planet first, with either inconvenient or dire consequences.

Reason two: the advanced alien lifeforms just weren’t interested in galactic colonisation, for either psychological or practical reasons.

Reason three: self-replicating machines have indeed spread throughout the galaxy, but the machines are hidden from our perception so that they don’t disturb us.

The whole television programme was about the possibility of life elsewhere in the universe (and was actually subtitled “Are We Alone?”), culminating in a discussion about intelligent alien life, so to dismiss the possibility of alien intelligent life on the basis of ‘no self-replicating machines’ without giving his reasons seems a bit lax.

Maybe he thought that the audience for such a programme wouldn’t be interested in arguments that were made in order to be dismissed, or maybe he just ran out of time (Time that could have been found, may I suggest, by cutting the silly sequence in which school children lined up with coloured lanterns to depict, very badly, the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram perhaps. Anyone who could make sense of that sequence probably already knew what the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram was).

Driverless cars – and how they may affect society

Travelling into the Future with No-one at the Wheel

Self-driving cars.

They’ll be fantastic.

It’ll be like everyone having their very own personal chauffeur, but one who doesn’t take up a whole seat and who doesn’t need to be chatted to or otherwise recognised as a human being who is inconveniently sharing the same intimate space as oneself.

The Jeremiahs amongst us may argue that such cars will keep crashing, that they’ll squash migrating frogs (which are already threatened with decimation by fungus) or that they’ll be used as suicide-driverless bombs, however the optimists among us know that technology will be able to take care of all of those things, so there’s no need to fret.

With driverless cars no one will need to pass a driving test anymore and everyone will be able to travel regardless of age or ability; children will be able to do the school run without having to take their fractious parents along with them; grown-ups will be able to go to the pub without having to draw lots to choose a designated driver; old people will be able to remain mobile well beyond the age where they would otherwise have to hang up their car keys. Everyone will be able to go wherever they want, whenever they want, simply by speaking a destination into the vehicle’s navigation system.

It’ll be a new utopian age of travel. Even better than the last one.

However, you know what utopias can be like.

Don’t imagine for a moment that the switch over to driverless cars will mean that everything stays the same other than the small fact that no one needs to actually do any of the driving anymore.

We may find our self-driving vehicles propelling us into a future that isn’t quite the one that we had in mind.

We need to navigate with caution.

The first, and possibly most predictable, change that driverless cars may usher in (other than the need for no driver of course) could be a sudden leap in commuting distances. People would be able to eat their breakfast on the journey to work and to catch up on their all-important social media interactions on the way home, all from the cosy bubble of personal space that is their self-driven vehicle.

The resulting extended commuting distances may entail more than a simple expanding of the commuter belts around our urban centres though – it may involve a mass migration of the population from the cities to the countryside. The ensuing rural building blight may be hideous to behold as houses sprout on former farmland (I say former farmland because we’ll probably be getting most of our food from Peru and Kenya by then, no doubt delivered to our shores and stores by self-navigating cargo ship and self-driving lorry). The concomitant blight on the cities due to the abandoned urban housing stock may ensure that, Detroit style, everyone but the most deprived of citizens feels compelled to up sticks and move countryward, whether they want to or not. If the value of city properties drops at the same time that those in the countryside rise, people may rationalise that they have little choice but to decamp to the country while they can still afford to.

The paradigm shifts brought about by driverless cars won’t only come in the form of major population shifts though, there’ll be massive cultural shifts too.

For instance, people may stop socialising locally and instead may socialise nationally (or even internationally).

This may be the antidote to the current epidemic of screen-only socialising, so in some ways it may be welcomed.

People may happily jump into an autonomous vehicle and travel huge distances of an evening in order to visit their friends or family. As long as people don’t spend more time in the car than they normally spend staring at digital devices they’ll still be in credit time-wise. As if that’d matter anyway.

In my youth (the 1970s) fun-loving people such as myself would be prepared to drive maybe a hundred miles or so to go to a friend’s party. But it’d be a major expedition – usually involving a mechanical breakdown while attempting to cross the Pennines in an overloaded Mini (version 1.1) – so we’d have to make a weekend of it. With driverless cars it’ll be possible to travel to parties at the other end of the country, and then to sleep off the hangover on the journey home before repeating the activity the following night. Hey! – why not just continue the party in the car?

This may not be too bad a thing if people just go round to other people’s houses for their personal interactions, but I can’t imagine that it’d stop there.

“Let’s meet at Stonehenge.”

Can you imagine it? Practically no tourist attraction will be spared the tsunami of visitors who will descend on it for birthday parties, hen parties, tea parties. Fortunately, parking the driverless vehicles once the passengers have been decanted won’t be a problem – despite the crowds – as the vehicles will either be hired in a similar way to taxis now, and will thus simply speed off on another journey, or they’ll be privately owned and will be capable of taking themselves off, passengerless, to any convenient parking space within striking distance, where they’ll wait patiently for the phone signal that summons them back to their owners. (When I say ‘phone’ here I’m referring to phones of the future, where the individual components of the phone are probably implanted biotechnically into the appropriate parts of the human body, thus obviating the considerable inconvenience of having to have the phone surgically grafted onto the palm of the hand as I think is the case now.)

The location of a destination will become irrelevant as the investment in effort involved in getting anywhere drops, with the decision about whether to visit a place becoming the result of a whim rather than of a complex analysis of investments, costs and benefits. The result will be that once distance is no impediment to visiting a place, the crowds who are visiting will probably become the impediment. This raises the spectre that because everywhere can be visited, nowhere will be worth visiting.

It wouldn’t be so bad if all of the visitors to a place actually harboured an interest in being there, but unfortunately quite a few of them will be there solely because being there is what people do. In many a historic stately home across the land the paintings lining the walls of the grand hall will be obscured by the hoards of glassy eyed zombies staggering along like an army of the undead in search of the teashop.

There’s an outside chance that island locations may partly escape the constant flow of visitors, as the journeys to them would involve a change of transport systems in order to reach them (at least during the infancy of driverless transport). Stonehenge may be deluged with visitors but the Ring of Brodgar may be spared, for a while at least.

Houses on islands may become extremely desirable places to live due to their isolation from the unceasing flow of whim-driven travellers on the mainland, making island living affordable only to the super rich.

The self-driving vehicle of the future probably won’t be like the car as we know it today of course, with two front seats, three back seats and a boot. It won’t simply be a car with no steering wheel. Not for long anyway.

It’ll conceivably evolve into something more akin to a spacious living capsule, complete with tables and chairs and probably beds. It’ll be like a sort of futuristic motor home, but one that doesn’t leave scratch marks on other vehicles because it’s misjudged its width.

But hang on – once you’ve got a futuristic motor home in which you can endlessly navigate the highways and byways of the world, why not do so? Why not navigate endlessly? Why not sell the house (that you’ve just bought in the country) and buy the luxury self-propelled living pod? Maybe the one with the built-in self-heating hot tub.

Give me one good reason why you wouldn’t want to do that?

Once you’ve got it, it’ll be first stop Stonehenge.